Artist portrait by James Jenkins

Artist portrait by James Jenkins

Jason Jägel

San Francisco based artist

Interview by James Jenkins

JAMES JENKINS: It’s May 7, 2016 and I’m interviewing Jason Jägel in San Francisco, California. Jason, tell me about your artwork.

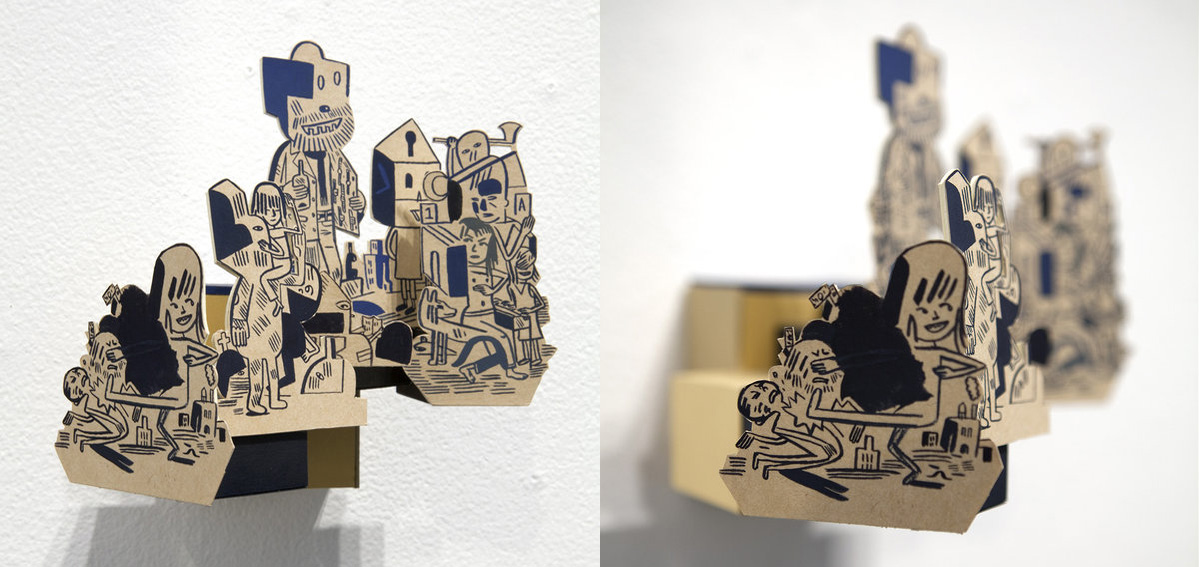

JASON JÄGEL: Primarily I’m a painter and a drawer, I guess, and drawing with paint. It’s hard to parse out those two disciplines, they both intertwine. I work a little bit three-dimensionally as well. I guess I’ve been interested in how 2D and 3D relate to each other, or how you can blur the line between the two.

City Living, gouache, paper, board, wood, glue, 5 1/4 x 6 1/2 in. ©2010

JENKINS: Do you have any training as an artist?

JÄGEL: As far as art training goes, it was really other artists around me that were the important part. As an undergraduate at CCAC 1990, it was through the social community there that would stay late every night, and we’d make art in the print shop or in the painting studio. It was through seeing those people that I feel like I got a large part of training, or influence, or inspiration. At the same time, stuff that I was bringing myself, whether it was music I was listening to, or there was all these great independent comics of the late ’80s and early ’90s that were super-duper formative to me at the time that they were coming out. As my own work was developing as a student, I was trying to figure out what it was I was going to do that made me feel satisfied that made me happy, basically.

“I have a practice where it’s largely based on improvisation and wanting to make something that I can’t necessarily preconceive, to me there was always something deadening about trying to preconceive.”

JENKINS: What do you think inspires and informs your creativity?

JÄGEL: I am invested in the idea that the artist and the person are one thing. I have a practice where it’s largely based on improvisation and wanting to make something that I can’t necessarily preconceive, to me there was always something deadening about trying to preconceive. Now I can frame it in the context of a rational brain or an analytical brain being brought to bear first to a creative situation. I ultimately want the opposite experience, or at least an inversely biased experience. I really admire idiosyncratic artists where the mythology of themselves as a persona and the way that they make art can be indistinguishable or convoluted. There’s something really wonderful about making something that I couldn’t preconceive.

JENKINS: Can we talk a little bit about that? Could you take me through some of those steps?

JÄGEL: It was just a survival mechanism, to a large degree. As a young person, as a young artist, living life itself didn’t feel particularly easy to me. Art was just something I did for my entire life. It was something I did compulsively. I recognized as an undergraduate art student that the stuff that I did compulsively was the important stuff. I just needed to take that from an informal context of scraps of paper, school notebooks, anything that was in front of me at any time when I was part way distracted, and take it into a formal realm of, let’s say, a big oil painting, or a sculpture, and to try to figure out … I was interested in trying to figure out what sculptural form can I make where I can make sculpture improvisationally, because sculpture often requires planning.

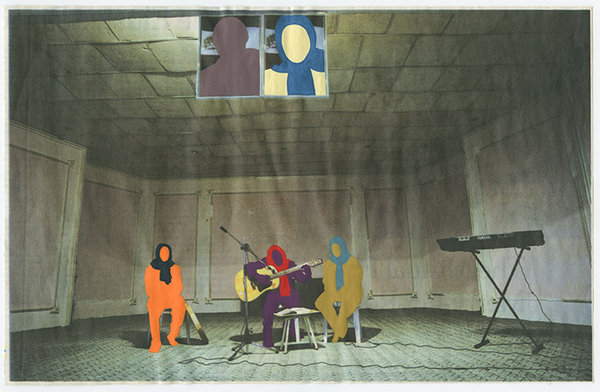

Skin Diver, gouache and acrylic ink on magazine, 3 x 4 1/2 in. ©2007

JENKINS: Can I focus just a second on this improvisation? Let’s say that you’re in the studio, and you’re going to work on a genre painting. Is there some sort of process that you do to get into that? Or is it that you go back and look at maybe things that you had doodled in a sketchbook while you weren’t thinking, or is it that you go and look around your studio to get information?

JÄGEL: Speaking historically, things that I would tend to do would be to work on a bunch of pieces at once, and working with gouache on paper is really a fluid medium for working improvisationally, because it’s non-toxic, you just clean up with water. Working on paper is incredibly immediate, requires very little preparation. All I have to do is mix colors. In some ways, actually, like the other day, my work in the studio started with me just mixing colors. I think that that’s a fabulous thing to do. It’s sort of like a foundation of my practice. Having been working now pretty consistently for a couple decades, there’s so much history that I’m always building on or coming back to or “tangenting” around in some sort of weird ellipse. There’re thousands of threads that I can pick up on at any given moment in my studio.

JENKINS: Is it fair to say that because of your 20 year practice your creative process, is now just innate?

JÄGEL: I can look at the last 20 years that I’ve spent largely with improvising. Things that happened to me along the way were I’d make a painting, and I’d have some success with this painting, let’s say. I’d make a painting that I admired, that did something for me. It was improvised. It was a result of an accident. Often times when I was a young student, it would be the kind of thing where I would smear out the entire painting, and then make something in a fairly short amount of time, usually, that was like this sui generis kind of thing that was built on the ashes of something were it finally managed to clear out my mind. Or it would be in the middle of a number of pieces, and I’d somehow get into some sort of groove where I was making more than one piece in a row.

Teenage Love ’69, gouache on newsprint, 7 x 11 in. ©2012

JÄGEL: Often times after I’d make a successful piece, I’d have the desire to make it again. I think that’s an innate desire, especially for painters or drawers, where you want to have that same experience, that same feeling of satisfaction. Ultimately whenever I did that, it would usually be a total car crash, a total failure, because I was trying to imitate the form as opposed to what made the form.

As a painter, you have basic rules, like never use color straight out of the tube, paint at arm’s length, step back often, those types of things that you set up for yourself and that are sort of part of the discipline in the traditional sense that you might pick up here or there.

I started to make other kinds of rules for myself. Never repeat yourself. Don’t work with a plan. Don’t try to do the same thing twice. Incorporate mistakes, incorporate incidental mark making in the form of arithmetic or phone call notations, things that you do compulsively, compulsive mark making, I guess is what it would be. Then along the way, work on multiple pieces at once. I can look back and analyze it and say, “Oh, what am I doing?” I’m prioritizing my spontaneous response to things. Your spontaneous response to things is one where your pre-frontal cortex doesn’t have time to spin up yet. You kind of dodge it. You can dodge it or prioritize the other, the less restrained, less restricted side of my brain by working that way, by jumping from piece to piece.

Modern Art, gouache & ink on paper, 22 x 15 in. ©2013

JÄGEL: I can then look at it analytically and be like, “Oh, it’s kind of this weird conversation I’m having with myself,” because when I step back and when I come back to something and I see it, I can say, “Oh, a cross. What does a cross mean to me?” I can expand upon that meaning, like a stone jumping across a pond, a frog jumping from lily pad to lily pad, rather than it being the result of one long consistent concerted effort. I get a lot out of that experience of going back and coming away.

That has roots to the compulsive form that I was doing where I’d be working in the margins of a school notebook, and I’d start something, and I’d start drawing, let’s say, a head. I at some point decide that it sucked and I hated it, and so I’d stop and leave it a fragment. Come back the next day. Instead of working with mechanical pencil, I’d have a ballpoint pen in my hand. I’d use a different material, and I’d pick it up. With that temporal distance from the experience, it could become something new. Those kinds of hybrid forms are what my art became along the way, because I guess part of it is looking back and analyzing what I’m doing, or noticing, observing what I’m doing. It’s like, “Oh yeah, it works quite well to switch materials, to allow myself to stop part way through. Let it be a fragment.”

A Million Steps, gouache, ink & pencil on paper, 26 x 40 in. ©2013

JENKINS: Where do you look for creative inspiration?

JÄGEL: I guess it’s the same answer, which is that it’s everywhere all the time. I’m sitting here drawing this little silly cartoon character head, but in my periphery, I can see your hand. I spend a fair amount of time in my periphery, whether I’m drawing and painting, or whether I’m out in the world. Gestures interest me, like when somebody puts a hand near their face, I’m looking at it in my periphery or directly. I’m visualizing it.

Hand -to-Mouth, oil on linen, 48 x 40 in. ©2014

JENKINS: Do you make art every day?

JÄGEL: No, I don’t, but luckily, I don’t have to. There are times I need to think about my art practice as a business, and if it’s going to sustain me and my family in the present and future. Being a studio artist is not my only role. I often will complain about my front office staff, and that’s because that’s me. If I’m not running a business, nobody else is. There are times where I come out to my studio and I’m like, “Well, there’s really no business reason for me to make art. There’s plenty of inventory here already.”

JENKINS: Interesting.

JÄGEL: That’s a bit depressing, honestly, because I’m a much better artist than I am a business person right now, possibly always.

“I spend a fair amount of time in periphery, whether I’m drawing and painting, or whether I’m out in the world. Gestures interest me, like when somebody puts a hand near their face, I’m looking at it in my periphery or directly. I’m visualizing it.”

JENKINS: How does the business side effect or interact with your creativity?

JÄGEL: I’m always looking for the opportunity to get a grant, or do a residency, do something that is business related that is something that allows me to be an artist. Working in a print shop is great, and it’s one of these kinds of experiences that you have where you can feel like an artist, and to have professional experiences that make you feel like an artist is really an incredible privilege.

JENKINS: Is there any part of approaching creativity or any part of the creative process that’s difficult?

JÄGEL: Absolutely. I think creation or creating, for me, is inherently challenging, is inherently difficult and can be conflicted quite frequently. I think part of that is that I’m not satisfied. I’m striving. I’m striving as best I can. I think I strive better and more as an artist than I do as a business person.

JENKINS: Do you think that there’s any sort of relationship between being dissatisfied and creativity?

JÄGEL: Absolutely. I think there’s that aspect of striving, which is not being satisfied, which is certainly positive. It seems like it’s all kind of wrapped up together, the potential for positive and negative, a feeling of joy and a feeling of suffering. It’s all pretty well wrapped up together in a productive form.

“There’s an aspect of my practice that was optimized for allowing there to be sharp, left-hand turns in the process, sometimes right before the finish.”

JENKINS: In the creative process, have you ever hit a wall?

JÄGEL: Part of my answer to that is the experience that I’ve had of incorporating tangents and mistakes into my practice itself. There’s an aspect of my practice that was optimized for allowing there to be sharp, left-hand turns in the process, sometimes right before the finish. If you think about making art as a series of decisions, I like it when some of the biggest decisions happen toward the end. It has a great dramatic effect.

JENKINS: What do you want your legacy to be?

JÄGEL: Oh my. There’s the practical side. There’s the vanity side, the ego side. God bless it. I would love to be recognized in all kinds of different ways for being artistically important. I’m important artistically to me, and I have a relationship to a wider world, and that’s wonderful. That’s plenty. Doesn’t need to be anything more than that. The practical side, I don’t know. I just often think about how if I wasn’t chasing bills all the time, what I could do. What I want from recognition is a little more ease in the creative life of being an artist, because it’s not fucking easy.

JENKINS: Do you have any advice for young artists or burgeoning artists?

JÄGEL: No.

When Pink elephants Fly, mural at Terminal 1, San Francisco International Airport ©2017

JENKINS: Anything that you could direct them toward or things to consider?

JÄGEL: In a sense, I obviously want to just encourage artists to not be reductive, to be stupid, and messy, and impulsive and to not make sense, to not fit into any kind of category that’s already set up of a professional artist, a successful artist, a conceptual artist, a painter, but to have this opportunity for creativity to be unshackled, to be unfettered. That’s kind of the most important part. I have seen all of these graduate students and so on where they’re in a school that’s asking them, “What are you about? What does this mean?” Those questions are for a rational brain. They’re for a pre-frontal cortex. That’s not the brain that works the best for me for making art. It’s not the brain that I like the most of the art that I admire. It’s confusing. I think it’s a complicated relationship for people to have.

There’s so much poison that’s out there, in terms of logistics of what it means to be successful. I can say I can see the importance in being unlimited or unfettered, entrepreneurially as well. That may be part of the destiny of the coming generations is that experience of creativity across studio lines into entrepreneurial lines, and having those two things be fluid and folding back on each other. I see people who seem to be like that. I admire them. I guess from a studio practice model point of view, if I admire them, I should start imitating them, because that would be a way to learn from them essentially. I think the thing about the marketplace is that it operates by … It has an ideology. I don’t think that that ideology is commensurate, or is the same, or is as important as the ideology of the studio. I’m inherently wary of the radio. I’m wary of the television. I’m wary of the computer. I’m the old dude who’s saying, “Goddamn etc., etc.”

More of Jason Jägel’s work can be viewed at: jasonjagel.com

Article edit by Mark Daybell

THE PRACTICE OF CREATIVITY

©2015-2020 All rights reserved