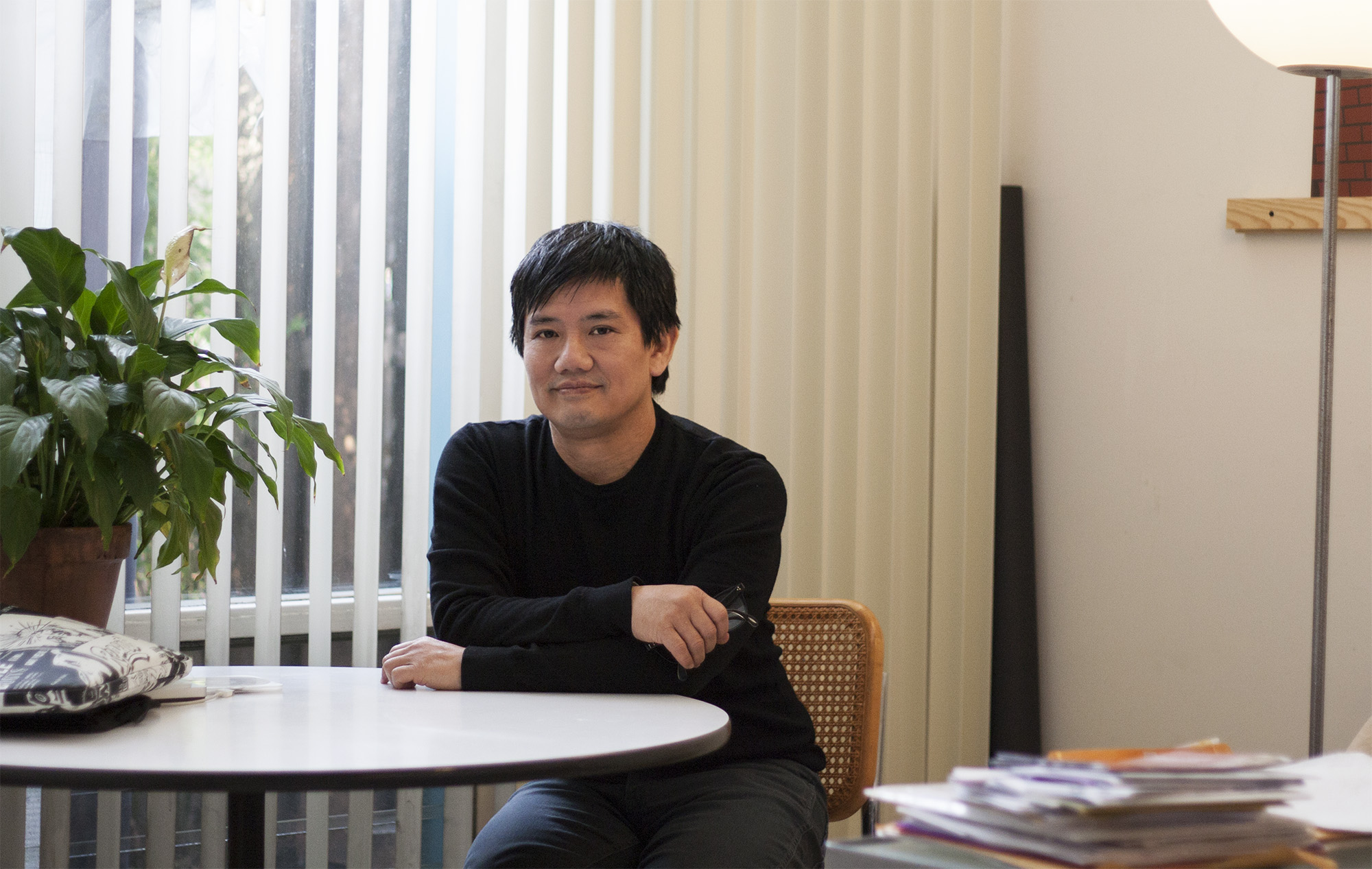

Artist portrait by Mark Daybell

Artist portrait by Mark Daybell

Simon Leung

Los Angeles based artist

Interview by Mark Daybell

MARK DAYBELL: It’s January 17, 2020. I’m here with Simon Leung, in his home in Silver Lake, California. Simon, can you tell me about your artwork?

SIMON LEUNG: Sure. I’ve been an artist for a long time and I think that mostly I work on projects. Meaning I think about making something through a long process and it’s not so much a particular kind of product that I’m thinking about, but rather a tone or a feeling that I have in relationship to something and I think about how that something should take up a form. Through the process of thinking about it and working on it and developing a form, developing a rhythm, that’s how I make a work of art.

DAYBELL: Are there reoccurring themes in your work?

LEUNG: Yes. I think there are some reoccurring themes. Since I was, I would say, maybe in my early 20s, I’d been thinking about the ethical relation broadly defined. And by that, I mean I think a lot about how we should approach something. The way I think about the ethical is not so much doing the right thing or making the right decision, but rather a type of difficulty that is inherent in the lived condition so that we prepare ourselves to face difficult propositions. Difficult situations. I think that most of my work is a meditation on that difficulty.

DAYBELL: Can you expand on that idea or highlight a project that explores this theme?

LEUNG: For about 30 years, I’ve been making work with the physically squatting body. What I’m interested in, in terms of the squatting body and the ethical is what one sees when confronted with this image and how this shifts in different contexts. So, in Berlin, when I made a project there in 1994, it was for an exhibition that dealt with violence against immigrants in Germany. For my project, I made 1000 posters and they pictured a squatting body from the back. You know, so you can barely tell that this is a non-Western body, non-European body. You get the idea that it’s probably an Asian body, but you don’t quite get who the identity of that person is or what the identity of that person is.

500 of the posters were surrounded by some text and 500 of them were blank. The ones that were surrounded by text, it was stated in German, “Proposal. One, imagine a city of squatters. A city in which everyone created their own chairs with their own bodies. Two, when you are tired or when you need to wait, participate in this position. Three, observe the city again from this squatting position.” So, for me, that work was really doing several things at once, right? It’s asking the viewer to think about this body that is being depicted, but also it suggests that this squatting position that this body is occupying is not an essential…it is not an essential way that this body exists in, because your body, when you are tired or when you need to wait, can also partake in this position.

The question then is why not? Right? Maybe because you cannot and maybe you cannot because the bodily techniques that you have grown up with has, in a sense, banished that position from your body.

I feel a project like this is really posing different kinds of questions. These are sort of ethical questions about what is the body of the other? You know? Isn’t the body of the other always, in essence, a body in fantasy? Because that body that is squatting is only temporarily squatting. That body will stand up and walk away. You know? A second later, a moment later. To me, the fragility of that temporary squatting position I think pierces a narrative of totality of national identity, of Western identification in a city like Berlin in 1994, because in a way, that body is comparable to all the other bodies that are in Berlin at that moment and what was, of course, at stake at that moment was the coming down of the wall and the West opening up. In other words, it’s really kind of a story about German self-regard. So, I would say that would be an example.

DAYBELL: Was “squatting” in any way referenced in the media at that time?

LEUNG: No. I had been thinking about squatting for a very, very long time and I actually wrote a text about this. When I was a teenager and my younger brother, three and a half years younger, he might have been a young teenager or he might have been 10 or 11 or something like that. I think it must have been around 1980 or just after 1980, because it was right after a lot of Vietnamese immigrants, former boat people, former refugees were resettled in California. So, my brother told me that he was at a bus stop and that he saw some Vietnamese people there. I asked him, “How did you know that they were Vietnamese?” He said to me, “Well, they were squatting. There were chairs there, but they were squatting.”

That immediately became kind of a painful moment for me, because it was as if I was watching my brother disassociate himself from other Asian bodies and it was as if assimilation demands that bodies which otherwise would have resembled his own, especially to, let’s say, “American eyes.” He was distancing himself from them and he was saying that this is strange, right? I just carried that image with me, you know, for, I don’t know, 15 years before I made a work of art about it. But that’s kind of my mode of working. By the time that I’m ready to make a work about something, it’s because I’m probably thinking about, if not the topic, I’ve been loitering in the neighborhood of that topic for a while.

“for me, there’s so much potential in not having complete control over something until you need to. It’s almost like until you actually bake it, it could kind of be anything.”

DAYBELL: What initially attracted you to art and art making?

LEUNG: I don’t know. But I can tell you that I did not have a plan B. I was a kid who was always interested in art.

DAYBELL: Like it wasn’t a choice, it just seemed natural.

LEUNG: Oh gosh, I don’t know. I think when I was very, very young, it was almost like art was a place and that place was where I wanted to go. I think when I was a kid, I didn’t feel that where I was living in either Hong Kong or in suburban California, I didn’t feel like those were places where I belonged. I felt like I belonged somewhere else and art was the place.

DAYBELL: Did you receive a formal visual arts education?

LEUNG: I did. I went to UCLA and Columbia and the Whitney program.

DAYBELL: What does your practice of creativity involve? Can you talk about some specifics?

LEUNG: I want to answer that as specifically as possible and maybe I can answer that through actually talking about process. So, when I’m working on something, one of my modes of working, which I’m comfortable with, but I understand some others are not, is I like to keep things open for as long as possible. By that, I mean, when I’m working on something, I usually have a sense of its shape. I have a sense of its rhythm. I have a sense of its way of being in the world, its duration. But I like it to be as flexible and as breathable as possible until I have to make final decisions.

So, what does that mean? I think that means, for me, there’s so much potential in not having complete control over something until you need to. It’s almost like until you actually bake it, it could kind of be anything. I always feel like, because I’m the only one living with the work, it’s not hurting anybody. It doesn’t really need to be anything until it announces itself as that.

Creativity, in that way of thinking or in my practical way of making art, it doesn’t have so much to do with a moment of origin as it has to do with an ethos of exposure, or allowing yourself to want to know more about otherness.

Sometimes this comes in the form of a particular person, like if you’re working with somebody, they might have a great deal to contribute in ways you never imagined or maybe there are ways they move or maybe there are some attributes they have that you didn’t quite know about.

In terms of working with people, it has a lot to do with you trusting other people. I think that is both an aesthetic decision and a type of question about how do you conceive of collaboration or authorship? It’s really ultimately a question of how do you want to be in the world.

“I think so much about being an artist is learning to not be afraid of failure. I don’t think I get excited about a work unless I could possibly fail.”

DAYBELL: I was thinking of your film, War After War and that it encompassed years and years of footage.

LEUNG: Yeah.

DAYBELL: And not worrying about what it is, while you’re making it.

LEUNG: That’s right. I’ve said elsewhere, we worked on it for at least eight years. I mean, who knows how long we really worked on it, because we started collaborating in 1992 and War After War was finished in 2011. It depends on how you count, you know, how long we’ve been working on it together. But for the longest time, for years and years and years, we were just working together without, quote, a film being the final product. It’s almost as if the film were a “by product,” to use that Hegelian metaphor of Warren and I working together.

DAYBELL: I think that’s a really great example of an approach that varies from the conventional, “I’m going to make a film. Where’s my subject?” The footage could also be 10 other things.

LEUNG: That’s right. I’m not very goal oriented. I’m drive oriented.

DAYBELL: Talk about how you begin a project.

LEUNG: It’s different every time, but usually something accumulates in me and I cannot get over it. Do you know this term “aporia?”

DAYBELL: No.

LEUNG: An aporia is an impossible situation. Now, there are many aporias that we face all the time, right? But the way I think about it is, something becomes interesting to me as something I might be able to do, if it remains difficult. If it remains, in a sense, unsolvable. So, if I have that feeling, if I can picture it in some way, if I can put a lens on it, if I can render it in some fashion, and if I see a possibility of pursuing something, then that’s how I begin.

DAYBELL: What is the role of chance in your creative practice?

LEUNG: That’s a very, very interesting question, because chance, especially since Duchamp, has been thought about and fetishized as a modus operandi. I think there is an element of chance in my work, but it usually is not the definitive organizing principle of the work. I think some of my works are more open than others and I think all works of art are received in a multitude of ways, much of which cannot be controlled by the artist.

I would say, on the level of reception, chance is something that is always just in the work, because we don’t have control over reception. In other words, there is no wrong way for an artwork to be received. I think it’s not a good thing or a bad thing, but I think it’s important to understand. I’m not someone who wants to control the reception of my work. I feel like I’m already controlling the reception of my work by making it.

“Creativity doesn’t mean for me something that starts with me. It means that it’s a particular type of condition that I avail myself of and maybe I have a chance of making a work with it or doing something with it, because I don’t think creativity begins and ends with me. I think of my work as a response to the creativity of others.”

DAYBELL: How does risk factor into your practice?

LEUNG: I’m not a risk seeker. But I sometimes choose to do something that is probably a little bit more difficult than I am comfortable with. But I don’t want to be comfortable. That’s the whole thing, right? I would rather do something difficult than to succeed by conventional standards.

Also, as I often tell my students, I’m not a physically courageous person but I do glimpse an extreme sport gene in the way I approach certain works. In terms of topic, but also in terms of its medium, I want to do something, if only because it would be thrilling to fail. I think so much about being an artist is learning to not be afraid of failure. I don’t think I get excited about a work unless I could possibly fail.

DAYBELL: How does the history of art and art making influence your process?

LEUNG: I don’t feel like I’m an artist who makes work for art historians. In my work, I’m more interested in the time somebody who experiences the work spends with the work than I’m interested in what they might recognize in the work in terms of references. I feel like it’s a poem. I mean, a poem is really comprised of language and the choice of the words. It’s not so much in how the whole thing sits next to everything else that is language.

DAYBELL: How do you recognize a good idea?

LEUNG: I don’t think a good idea is enough. In fact, one of the things that I emphasize is that to me, all great art has to be wrong on some level. Often times I think some works of art are not wrong enough. Now, that doesn’t mean I’m fetishizing bad art, right or bad painting, but I think that a work of art, for me, is not really about the quality of an idea, but how you stay with a thought.

When you have spent most of your life thinking about art, looking at art, being with art, the thing that you’re really looking for, I think, is something within that object or that hour, that experience, that is intense. Maybe not in a literal sensory way, but you want it to matter. You want it to not be everything else you’ve seen. So, it’s that quality of how it is different from everything else you’ve seen that I think I’m interested in.

DAYBELL: Do you ever hit a creative wall and how do you break through it?

LEUNG: I would say that in the last 20 years or so, there might be years in which I don’t make something, but I’m actually always working on something. The first 10 years, let’s say, of showing my work publicly, was pretty intense. And then after I made a big project called Surf Vietnam in 1998, I essentially stopped working for a couple of years, because I was exhausted. I think sometimes you just get too tired, because you’re invested, because you’ve put too much into your work and you need to get back to life before you can make work again. I think part of what it means to continue being an artist is managing, regulating that economy of emotions that comes with making work.

DAYBELL: What inspires or informs your creativity?

LEUNG: When I see performances or films or read something, I’m often thinking about translating it into something else. In other words, when I’m listening to somebody give a talk, when I’m reading a passage from a book, or theoretical text or something, I’m often thinking about responding to it and how I would respond? Often, that is through something I have already been working on. I would say that’s a constant thing. It’s not so much something inspiring or informing me, but I feel that I’m often stepping back into my own work when I am reading something or when I’m watching a performance.

Creativity doesn’t mean for me something that starts with me. It means that it’s a particular type of condition that I avail myself of and maybe I have a chance of making a work with it or doing something with it, because I don’t think creativity begins and ends with me. I think of my work as a response to the creativity of others.

DAYBELL: What advice would you give emerging artists?

LEUNG: Well, I guess it depends on what type of artist. I would say do the more difficult thing.

More about Simon Leung can be viewed at: https://art.arts.uci.edu/simon-leung

Article edit by Mark Daybell

THE PRACTICE OF CREATIVITY

©2015-2020 All rights reserved