Artist portrait by James Jenkins

Artist portrait by James Jenkins

Willem-Henri Lucas

Los Angeles designer

Interview by James Jenkins

JAMES JENKINS: It’s May the 26, 2016 and I’m interviewing Henri Lucas in his apartment in Los Angeles. How long have you been a graphic designer? Could you talk about that journey?

WILLEM-HENRI LUCAS: Let’s see, I was 21 when I graduated and started working immediately. First, I did an art magazine called “Metropolis M.” It was, and still is, one of the most important magazines on contemporary art in the Netherlands. It was a bi-monthly magazine, and it gave me enough income to rent studio space. That’s how I started, basically, and then I mostly worked for recently graduated theater majors, dancers, choreographers etc. with all subsidized projects, for very little money. I had to at least have five of these assignments a month to make a living, but that worked out fine.

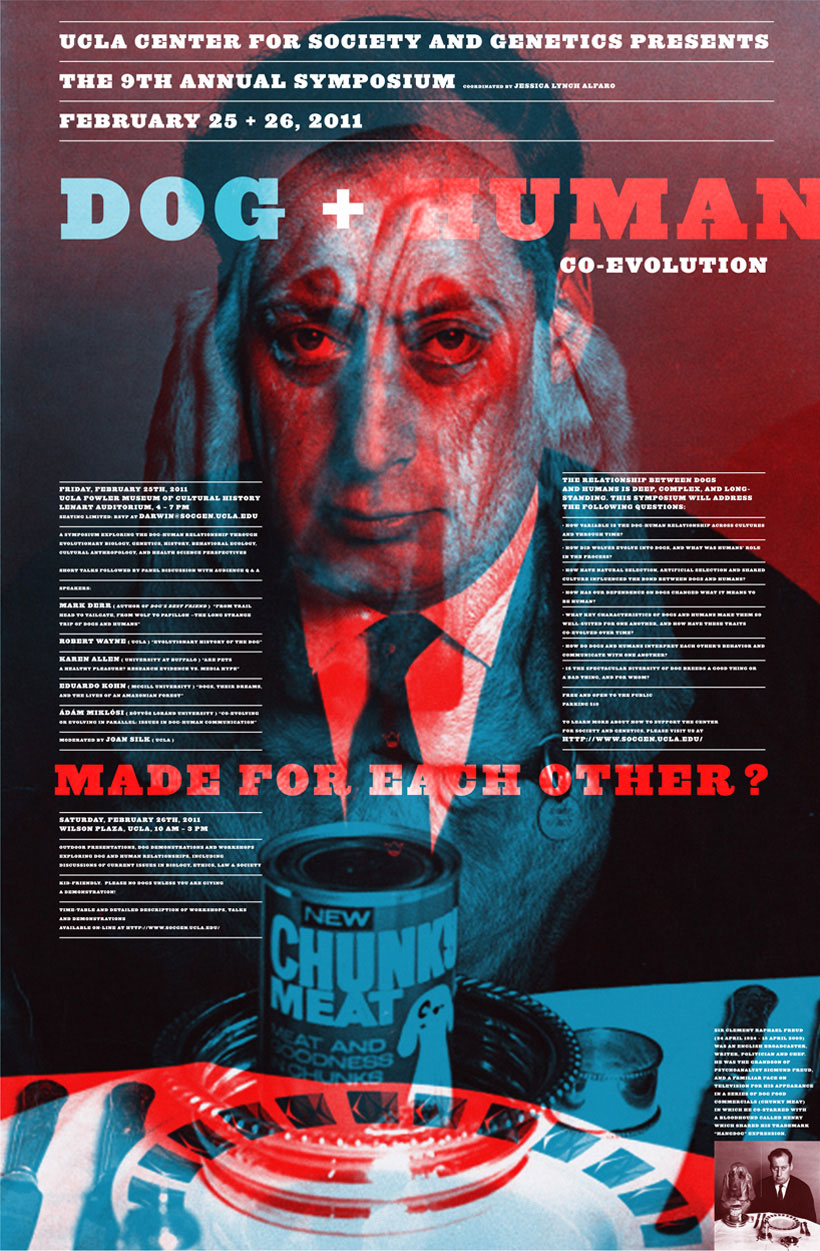

I know so much about the offset press because I had to be very smart about how I printed stuff. I experimented with things like printing without black and not using CMYK but a stronger blue, a stronger red and a stronger yellow so that their mix would be much darker and make a black. In that time, you basically paid for how many times the paper went through a press. I could make print work that was less expensive than full color by using spot color inks. Funny enough, I got the reputation that I made very expensive print work, because it looked different, people automatically assumed it cost more.

JENKINS: Were you educated in graphic design?

LUCAS: I went to art school in ‘79 at the Academy for Fine Arts in Arnhem, which was one of the most typographic academies at that time. There are 15 art schools in the Netherlands. They all differ somewhat in what they offer. The Hague and Arnhem were the two ones with Graphic Design departments that were known for typography. It’s kind of funny that I ended up there, because at the time I had no clue what typography really was, I was much more into illustration and photography.

JENKINS: What led you to book design?

LUCAS: I have always been a lover of books. I am still an avid reader. Funny enough, it didn’t start with book design, I was really into magazines. I did my internships at magazines in the Netherlands. I also think my typographic skills were not up to par yet to consider book projects, but slowly it became more of a focus. I am really interested in the editorial part of the design. I’m into text. I’m into using text as a starting point to figure out how it needs to be designed. More and more I became co-editor of the publications that I designed. Now I’m fully taking the editor’s role. I think it sort of grew into where it is now.

“Language is also very important because I know many of my inspirations or work comes from reading text and interpreting it in a certain way.”

JENKINS: Do you have any projects outside of your design practice that inform your studio work or inform your design work?

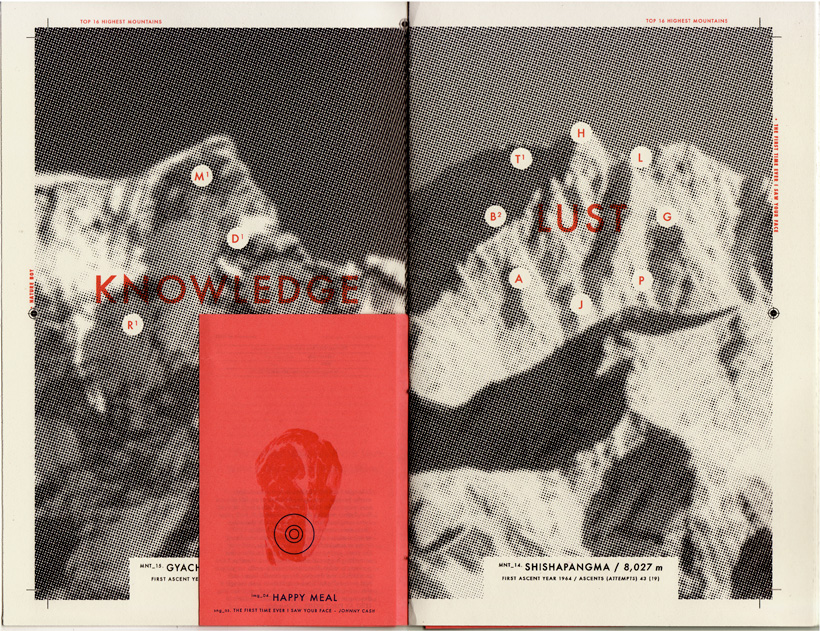

LUCAS: There’s a couple. One that’s very close to my design practice is the Reader publication that I do with five other designers. Every winter and summer we make a publication in an amount of 100 copies. We’ve been doing that for the last five years. We are the designers, as well as the researchers, as well as the editors. It basically takes out the whole client situation in graphic design and is a direct communication between designer and audience.

Winter Reader, December 2011 – On Love: Obstacles and Mixed Messages

LUCAS: That’s one. Then I actually do a lot of stuff next to design. Many of them have to do with fabrics and textile. I took up sewing clothing items for myself. I made those bunnies on the couch which are an ode to Joseph Beuys, but I also make tapestries.

Rabbits for Joseph Beuys, 2015

LUCAS: What I did with these lowres video stills was basically mess them up by shifting the CMYK layers in Photoshop, and almost make sure they fell apart, I then looked for a loom that would weave it back together. What happens is that these very tiny stills blown up, are incredible when you’re up close to the fabric. You see only lines and abstract imagery. If you take distance you see the image clearly. It got woven back together. I like textile. I’ve worked with a couple of textile designers. I have a big love for fabrics and textile design.

JENKINS: What does your practice of creativity involve? Can you talk about some specifics?

LUCAS: A creative process, I think, in many ways starts with knowledge. Having seen lots of art, you can never see art enough, and the more contemporary, the better, but also know the historic overview of what reacts to what, and the connections between the old and the new. That knowledge is incredibly important because you tap into that, the minute you start on something new. That’s just something you need; to read, to look up books, to see exhibitions, go see movies, and listen to music. It’s all the disciplines together, basically.

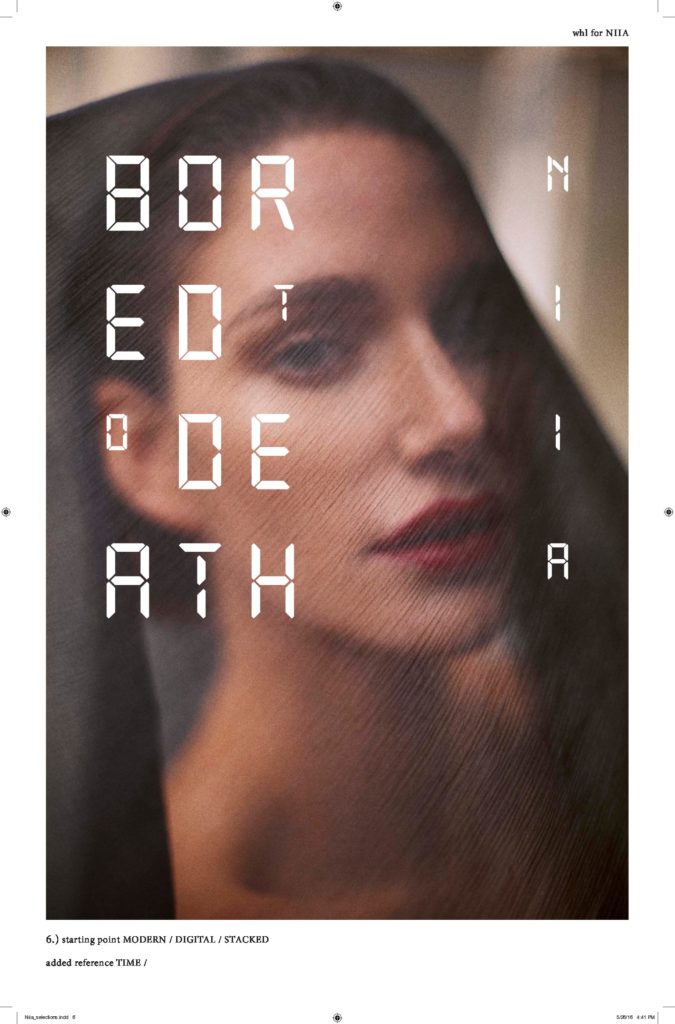

The other part is a way more technical part and that is being able to do research. Language is also very important because I know many of my inspirations or work comes from reading text and interpreting it in a certain way. It’s important to make connections between visual meaning and the meaning of text. When I was working on a music cd cover for recording artist Nia called Bored to Death, I was like, “What does that mean, a sentence like ‘bored to death’?” It has to do with time, and having too much time. At some point I chose a digital typeface to set the title, just to see what the effect would be. It shows how much meaning you can give a certain text when you’re playing into the meaning of what it actually says. The literal meaning of words can help you get form or get form choices. I think (text) analysis is something that is incredibly important with creativity.

Airplane crashing on water, May 2015

LUCAS: I also think creativity is you jumping from one thing to another. Jumping from visual ideas to text ideas to form ideas is what is constantly going on because you’re making connections to all sorts of things.

Being able to make a lot of references in your work. For instance, with books, I love footnotes. The longer and the more, the more interested I am. I have the same interest in imagery that brings up a lot of other images, because references to me are interesting, they make the brain work. You’re trying to figure out where have I seen this image before, and what does it mean? When I was teaching in Utrecht (Nl.), at the School of the Arts, I worked for 3 or 4 years with a semiotist. She was interested in my work because she said, “It’s interesting how many references you put in your work.” Which I did intuitively. It was not like I had very clear understanding of what I was doing. I think semiotics taught me why. It’s very important if you want your audience to have a dialogue with your work, to keep them intrigued as long as you can

Niaa – Bored to Death CD cover proposal, 2016 rejected design by Luke Gilford

Dog + Human co-evolution poster, 2011

AIGA LA student portolio review poster, 2007

Shakespeare at UCLA: Romeo + Juliet poster, 2008

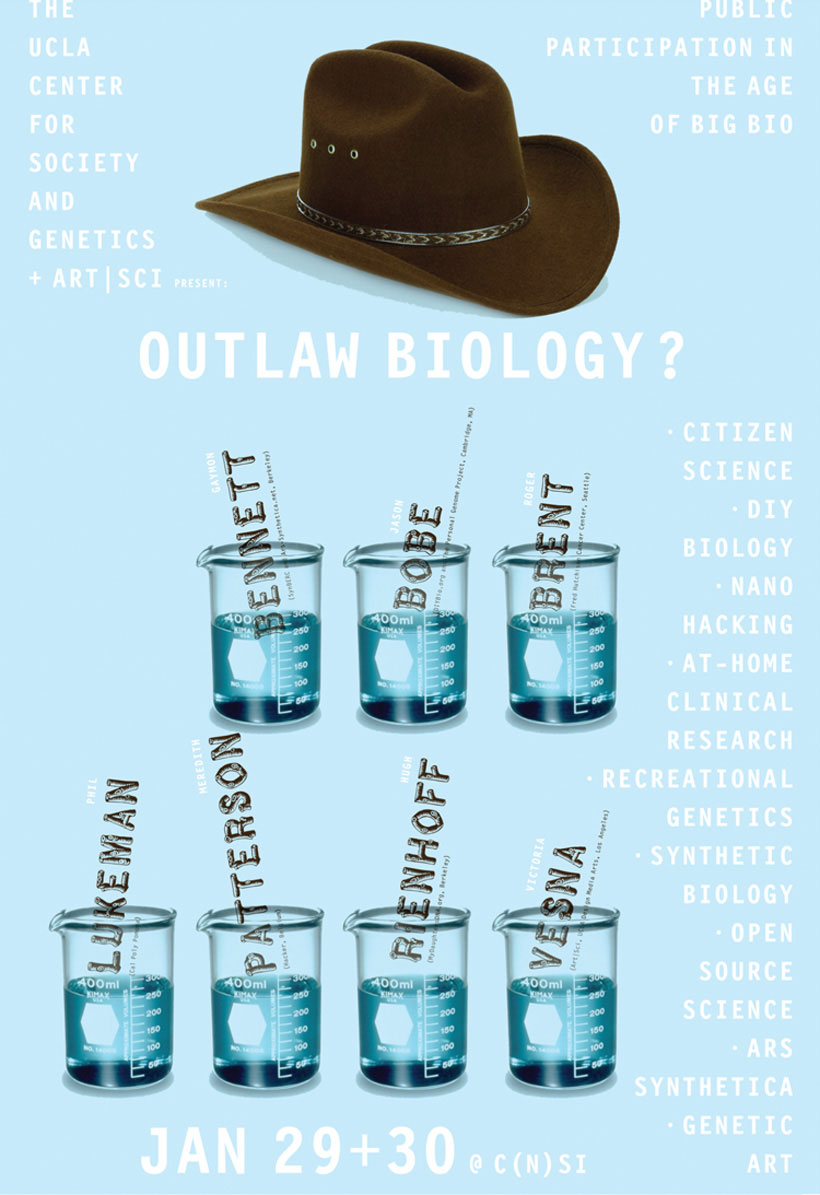

Outlaw Biology poster, 2010

JENKINS: How do you record your ideas for projects? For instance, do you draw? Do you keep a sketchbook?

LUCAS: It depends on how big the assignment is and how long I can work on it. If it’s a big assignment, I make process books. I do save all my InDesign files. I’m also not embarrassed about my first designs, even if I know they’re horrible, but my making them those first ideas get out of my head. I’m also a designer who needs to produce a lot to come up with quality work.

“The best moments in the creative process is where I discover something new or something that I had overseen or a new point of view.”

JENKINS: Do you design every day?

HENRI: I do.

JAMES: Is there any role of chance in your creative practice?

LUCAS: I think so. The minute I start with an assignment I try to start completely blank, even if I know stuff about the subject matter, I throw away all that knowledge. The best moments in the creative process is where I discover something new or something that I had overseen or a new point of view. Since you don’t want to repeat yourself, those are the things that you’re looking for in your process. I think that’s the exciting part. It could be anything. It could be a quote or it could be one image that makes you look at things completely different.

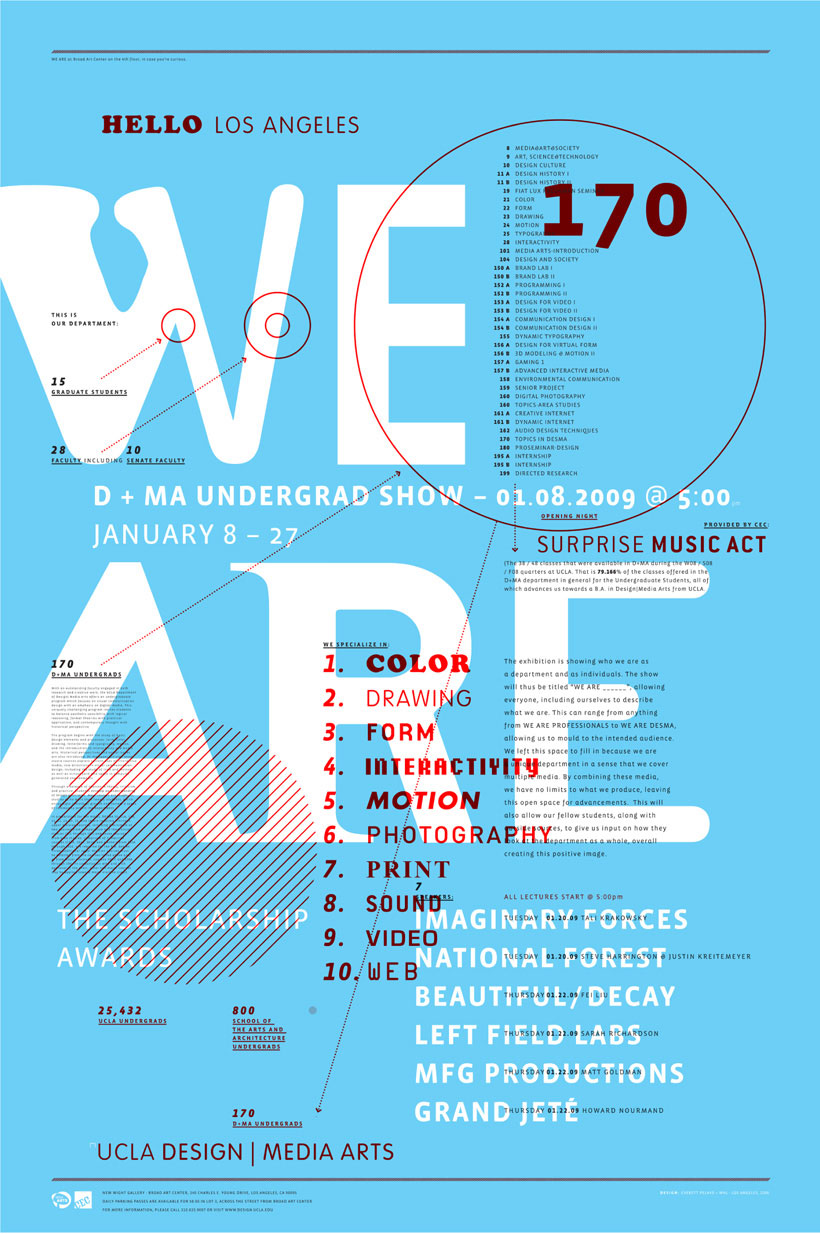

We Are, poster designed with Everett Pelayo, 2009

JENKINS: Is the creative process a challenging process for you?

LUCAS: Yes and no. I’ve been designing for almost 35 years. By now, I know that when I commit and when I start … the commitment is really about endurance. It’s about not giving up and diving into the subject matter. I know that if I do that I’m able to come up with something. Whether it’s brilliant or whether it’s okay, is another question. However, it’s never easy because I force myself to start at zero every time. It doesn’t really matter how much I know about a subject matter, you just go over it again.

JENKINS: Do you need to be in your studio in order to access your ideas?

LUCAS: No. I can practically design everywhere. I used to be able to do that even without a computer …now I’d be lost, I would say. I can hardly separate myself from my computer anyways. Ideas come and go. I can honestly say that some ideas came while I was sleeping, and then I go out of bed and write something down on a piece of paper, and try it out as soon as I get up. I once made a book (Polar Inertia on migrating systems) and it has big titles on the pages, but there’s a page in between so you see half the title and when you flip over the page the rest of the title appears. I literally dreamt that in my sleep and then I wrote it down and used it. I used to have a box in my studio with ideas. 4 or 5 written lines, on anything; ideas for a movie, ideas for a drawing, ideas for a book. I stopped doing that. That was a fun box to look through at the end of the year.

“I have a very organized design process with steps. Even if I have to make something that needs to be finished at the end of the day, I go through all these steps. I go through all these steps also if I work on a book for 2 years.”

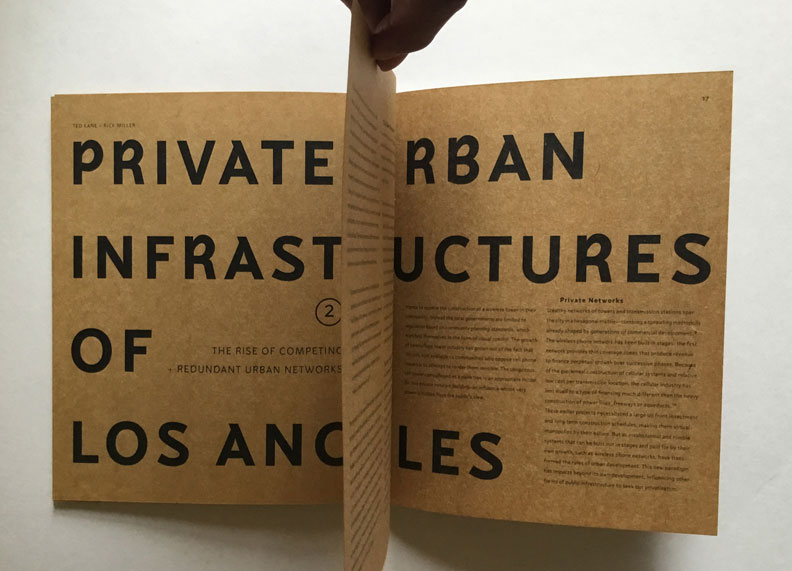

Ted Kane – Polar Inertia, book design with Davey Whitcraft, 2007

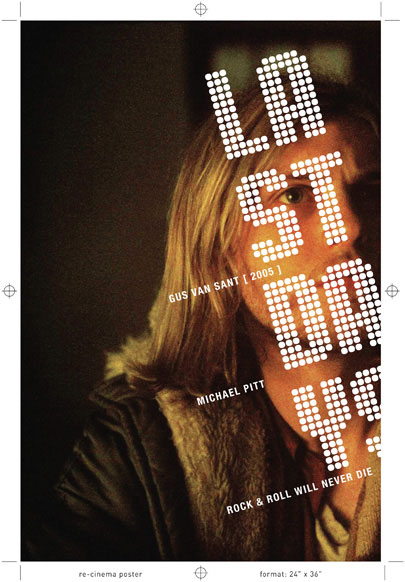

Last Days, Re-C-nema poster, 2012

JENKINS: How do you know when a design project is finished? Can you talk about some of the decisions that decide that?

LUCAS: The first one that decides that is time, I have to say. I have a very organized design process with steps. Even if I have to make something that needs to be finished at the end of the day, I go through all these steps. I go through all these steps also if I work on a book for 2 years. It’s like you constantly adjust. If I have 8 hours to make a poster and I want to start fresh and blank, then I need to use the first hour “googling” as much stuff and information that surrounds that subject matter.

If I have 2 months for that poster, I use 1 month to capture as much information as possible. It really starts with dividing and planning time. The other thing, sometimes you’re in the midst of a process and you make something based on certain starting points. Sometimes you know that it looks so good that it might not matter how long, how much more designs you make, but you can’t top that one design. That’s really difficult. I force myself to usually go on, but I will also be realistic enough to go back to that one design that I think was good. Sometimes everything just falls in its place, and you feel this is it. Wait, I had 2 weeks for this thing and I only worked on it 2 days. It’s a tough thing to sell to yourself, but also to the people you work for.

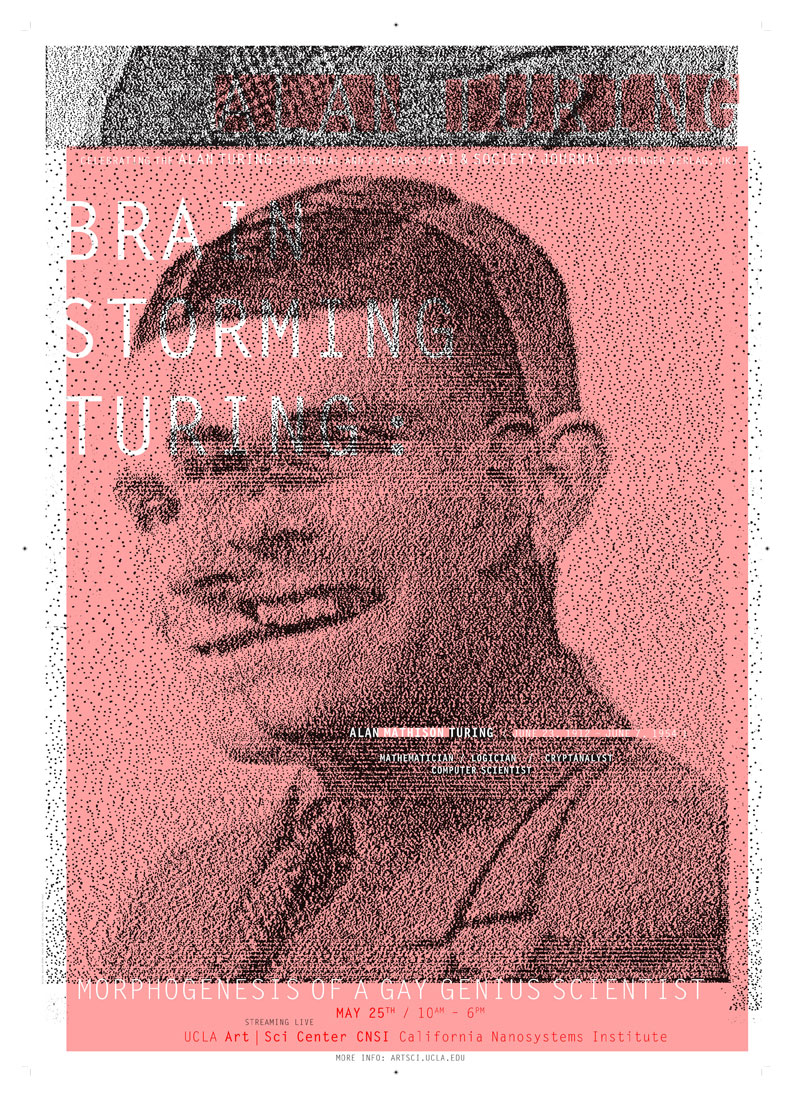

Brainstorming Turing poster, 2012

JENKINS: Do you look at contemporary trends in design?

LUCAS: I do, I have to.

JENKINS: Do those influence you?

LUCAS: No, weirdly enough. Trends are so connected to time, usually they’re made by a younger generation that looks at form in a different way than the way I grew up or the way that I was educated. I’m always very happy that I do not have to make that kind of work. However, it’s really important to look at trends because it will bring a shift of possibilities. For a very long time now, there’s been a shift toward anti-design. I’m interested in what is ugly and what is beauty. I think there’s no difference.

JENKINS: Are you satisfied creatively?

LUCAS: Absolutely. I chose a discipline which is graphic design. I wish I could know as much about filmmaking and I wish I could know as much about video or art making, for that matter. I wish I could do all of that next to each other. I’ve always been someone or I always felt that I could do a little bit of everything. My peers have always denied that and said, “No, you’re a total specialist in that, that and that.” I also have a weird relationship with fashion. I find fashion highly intriguing, but I find it superficial as well. It does reflect the entire society, which is the interesting part. All these things to me have incredible connection.

JENKINS: What advice do you give to young designers or to burgeoning designers?

LUCAS: I think starting as I did with really reading a lot, really seeing a lot, get extremely involved in art and culture and society as well. Be extremely committed and responsible. In art school, I had this moment where I was super convinced that if you are to become one of the image makers or visual makers of your generation, you should represent them as truthful and with as much integrity as possible. That’s a whole different set-up than I just want to make beautiful stuff. It’s that responsibility and being part of what happens in the world and being part of a dialogue that I felt was extremely interesting and challenging. But also, I felt extremely responsible as in I don’t want to make certain imagery or I don’t want to be part of certain communication streams.

In the meantime, you learn so much about yourself. I think it’s really important to express these things because I think in general graphic design is not perceived as such. To also make sure that all the work that you create needs to look like it’s made right now in the time you are living in, therefore, it should document time. It should document what you were interested in. To actually have a body of work that in the end shows who you are as a person. That is another way of looking at this profession and not be driven by money. I’m not against surviving, don’t get me wrong. The rent needs to be paid. In the beginning you take whatever job you can get. I just ran into issues of getting extremely unhappy, if I had to work for something that I was not part of. Although, I can honestly say that if I was against it the subject matter at hand, I’ve always said NO. That becomes an ethical issue. I was very aware of that, when I was in art school.

I don’t think that many people look at design that way. It’s getting more and more difficult because the world that we live in is way more commercial than the Bauhaus times, to just name one. It’s interesting if you read books about the Bauhaus and its founders how social and political it was. I actually find it very important to always go back there, the only things that makes you stand out in the crowd are your own beliefs, your own privileges, and your own references. For me, it’s very much about being informed and staying informed.

More of Willem Henri Lucas’s work can be viewed at: cargocollective.com/willemhenrilucas.com

Article edit by Mark Daybell

THE PRACTICE OF CREATIVITY

©2015-2020 All rights reserved